AVALANCHE RISK MANAGEMENT WITH D-C-M-R

In order to turn information and knowledge about avalanches into sensible decisions during planning and while in the mountains, we need a decision-making STRATEGY. This will help us come to the most precise possible assessment of our RISK. Bear in mind: Mountains represent a dangerous environment, where we bear responsibility for any consequences. There is no absolute safety: We can only reduce the risk to a level we are comfortable with by assessing it and coming to a decision. The D-C-M-R METHOD has established in snow science in recent years. It follows the equation:

D + C - M = R

The DCMR risk assessment method provides a structure that incorporates all the relevant areas.

D stands for danger, meaning the probability of an avalanche.

C stands for the consequences that result from an avalanche.

M stands for the measures or possible actions people can take to influence the first two points – danger and consequences.

Finally, R is the resultant risk.

The “people” factor plays a key role in the measures that can be taken and regarding the consequences and danger of an avalanche.

D = Danger

Here, we limit ourselves to the main danger for ski tourers and freeriders: the snow slab. However, D can easily be extended to other dangers such as falling, cornice breaks, falling into a crevasse, hypothermia, etc.

As previously explained, the probability of a slab avalanche depends on the four “ingredients” for a snow slab, i.e. unfavorable layers, initiation, crack propagation and the required steepness.

Therefore, in the complex version of danger assessment, we ask ourselves the following questions one by one:

-

Is there a snow slab with a weak layer beneath?

-> No? Then I can ski the slope.

-> Yes or I don’t know? Continue to the next question.

-

Can I stress (initiate) the weak layer?

-> No? Then I can ski the slope.

-> Yes or I don’t know? Continue to the next question.

-

Can the crack in the weak layer propagate?

-> No? Then I can ski the slope.

-> Yes or I don’t know? Continue to the next question.

-

Is the slope steeper than 30°?

-> No? Then I can ski the slope.

-> Yes or I don’t know? Continue to the next question.

That’s the theory. In practice, the question about the weak layer is often difficult to answer. The questions about initiation and crack propagation are even more difficult. Only the steepness can be easily and reliably determined.

Therefore, winter athletes who are not avalanche experts must be able to assess D, the probability of an avalanche. Different questions are required depending on the training and experience of the person.

Therefore two different methods are outlined here: one for the less experienced and one for advanced persons.

Simple danger assessment on individual slopes

When evaluating the probability of an avalanche (D), less experienced users should limit themselves to the following four questions:

Warning signs are a clear indication of a volatile avalanche situation. This applies at least to the areas in which they are observed or perceived (slope aspect, elevation, terrain features). If the answer to the first question on warning signs is “quite often” (orange) or “often” (red), you should take extremely defensive action in these areas.

Fresh tracks on the slope are an indication of safety; in 90% of cases it is the first person to travel on a slope that triggers the slab. Therefore, tracks suggest that triggering is unlikely or that there was evidently no crack propagation.

Be careful in the event of persistent weak layers or individual tracks in areas with lots of snow! Unlike new snow or wind-drifted snow problems, when there are persistent weak layers it is less the lack of additional load that keeps a slope from sliding (yet); rather, it is likely that the slope has not yet slid because the crucial area in which the weak layer is close enough to the surface has not yet been “hit”. Therefore, tracks aren’t much of an indication of safety when there is a persistent weak layer problem.

Slope steepness correlates with the probability of an avalanche. In other words: the steeper the slope, the more dangerous! Regardless of the danger level issued, on average, avalanches triggered by winter athletes happen on slopes with a steepness of 38°.

This means: Most avalanches occur on slopes between 36° and 42° in steepness. Therefore, slope steepness is a legitimate criterion for estimating the probability of an avalanche.

Statistically, the danger level should not really apply to the individual slope; however, it is roughly accurate. This means: When the danger level given in the avalanche bulletin for the zone you are travelling in is actually accurate, it is more likely that you will trigger a slope at a higher danger level than at a lower danger level. Therefore, using the general danger level as an assessment criterion for an individual slope is definitely a legitimate method – despite the justified criticism that a general danger level is by definition not applicable to an individual slope.

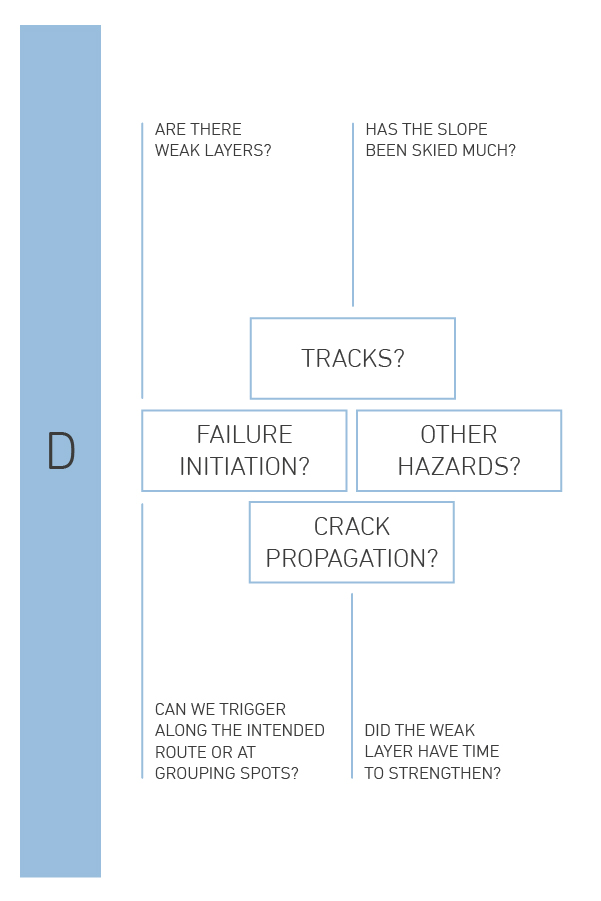

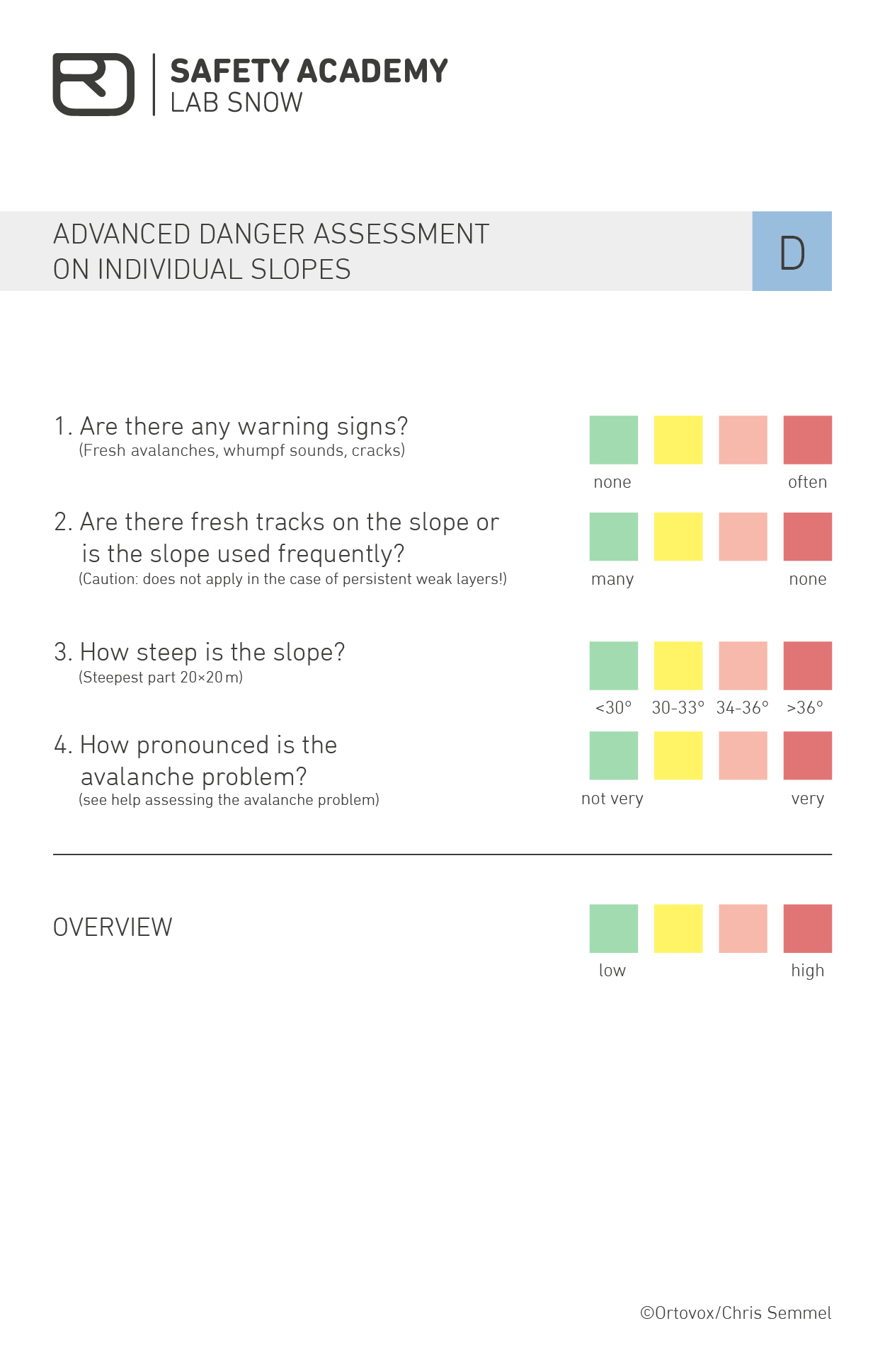

Advanced danger assessment on individual slopes

Advanced users who can identify and evaluate avalanche problems should ask themselves the following questions:

Warning signs are a clear indication of a volatile avalanche situation. This applies at least to the areas in which they are observed or perceived (slope aspect, elevation, terrain features). If the answer to the first question on warning signs is “quite often” (orange) or “often” (red), you should take extremely defensive action in these areas.

Fresh tracks on the slope are an indication of safety; in 90% of cases it is the first person to travel on a slope that triggers the slab. Therefore, tracks suggest that triggering is unlikely or that there was evidently no crack propagation.

Be careful in the event of persistent weak layers or individual tracks in areas with lots of snow! Unlike new snow or wind-drifted snow problems, when there are persistent weak layers it is less the lack of additional load that keeps a slope from sliding (yet); rather, it is likely that the slope has not yet slid because the crucial area in which the weak layer is close enough to the surface has not yet been “hit”. Therefore, tracks aren’t much of an indication of safety when there is a persistent weak layer problem.

Slope steepness correlates with the probability of an avalanche. In other words: the steeper the slope, the more dangerous! Regardless of the danger level issued, on average, avalanches triggered by winter athletes happen on slopes with a steepness of 38°.

This means: Most avalanches occur on slopes between 36° and 42° in steepness. Therefore, slope steepness is a legitimate criterion for estimating the probability of an avalanche.

An especially important factor in assessing individual slopes is the evaluation of the avalanche problem. Can I identify an avalanche problem on the slope and, if so, how precarious does it seem to me? These questions can be answered with the help of the five questions listed under each of the avalanche problems.

These two structures – simple and advanced danger assessments on the slope – give us an estimation of the danger (= probability of an avalanche) on the individual slope.

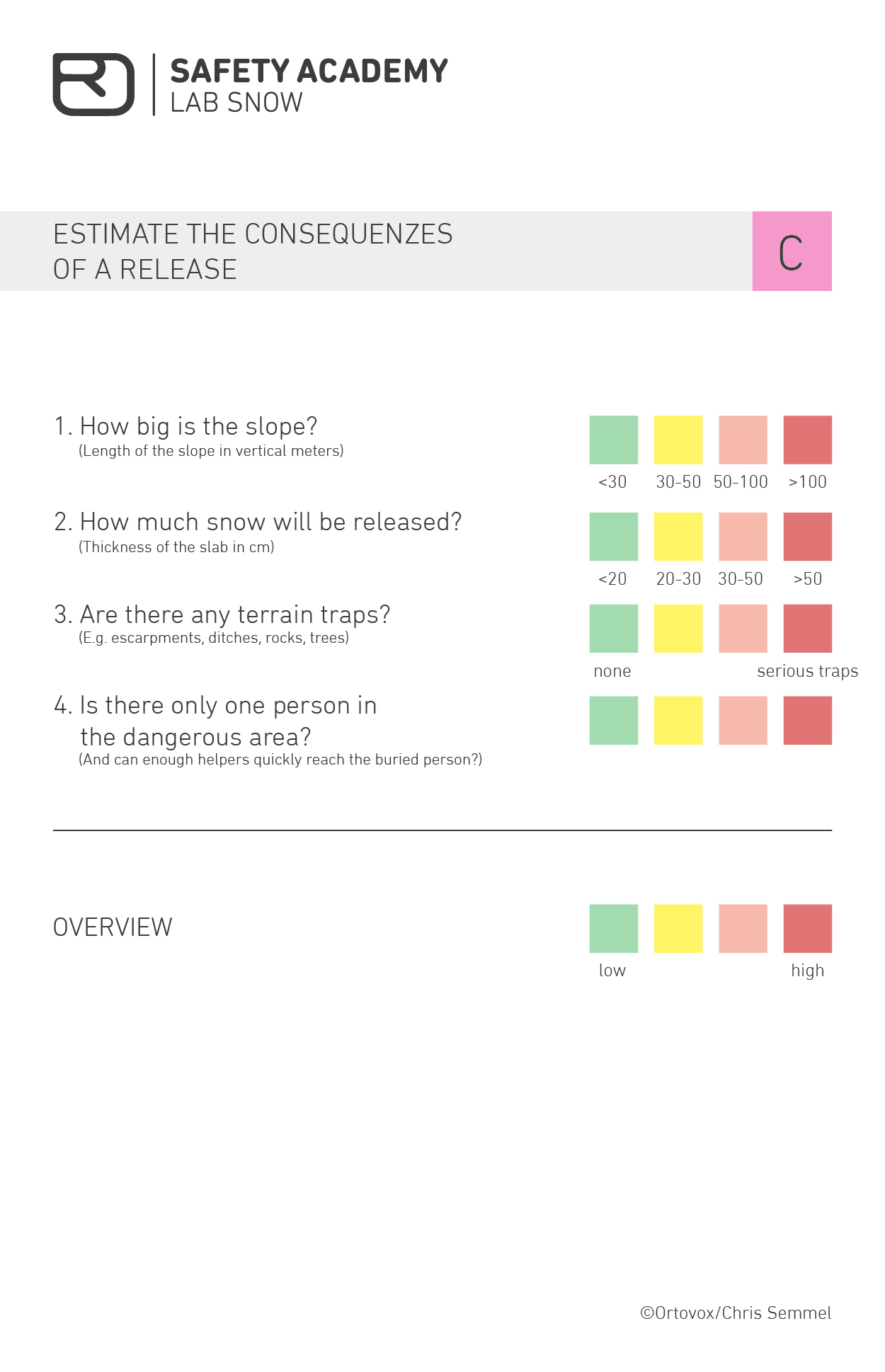

C = Consequences

Unlike the probability of an avalanche, the consequences of an avalanche seem relatively easy to assess. For this reason, we don’t need different methods for different user groups.

When assessing the consequences of a slab avalanche, we address four relevant questions:

The size of an avalanche slope correlates with the burial depth or mortality rate of an avalanche. This means: The more slope above you, the deeper you will be buried and the more drastic (fatal) the consequences. Being below or at the bottom of an avalanche slope is more dangerous than being high up on the slope. But the flow path length of an avalanche also impacts the chances of survival. It is difficult to determine exactly where a limit is. As usual, we need to make do with uncertainties when evaluating avalanches and their consequences. One positive thing is that you can use a map to assess the slope size during the planning stage.

The volume of snow also correlates with the consequences of an avalanche. A 30cm-thick snow slab has lower destruction and burial potential than a slab 60cm thick or more.

To estimate the thickness of a snow slab, you need to have a rough idea about the position of the weak layer. This is easy when it comes to a classic new snow or wind-drifted snow problem, in which the weak layer is often constituted by the old snow surface. But it is significantly more difficult if there are persistent weak layers. Due to its high density, the risk of dying in a wet snow avalanche is significantly higher than with a dry snow slab of the same thickness. Therefore, on closer inspection, there are also some uncertainties here that we need to learn to deal with. Using the description of the snowpack and the current snow profile on the internet, you can make a rough assessment during the planning stages that should be verified once you’re in the mountains.

Terrain traps are often the key criterion for assessing consequences. An escarpment in the avalanche path can often be fatal. Rocks and trees in the path of an avalanche often lead to serious physical injuries. Bowls and ditches can result in deeper burials. The positive thing about terrain traps is that you can assess them during the planning stage based on the map and terrain relief.

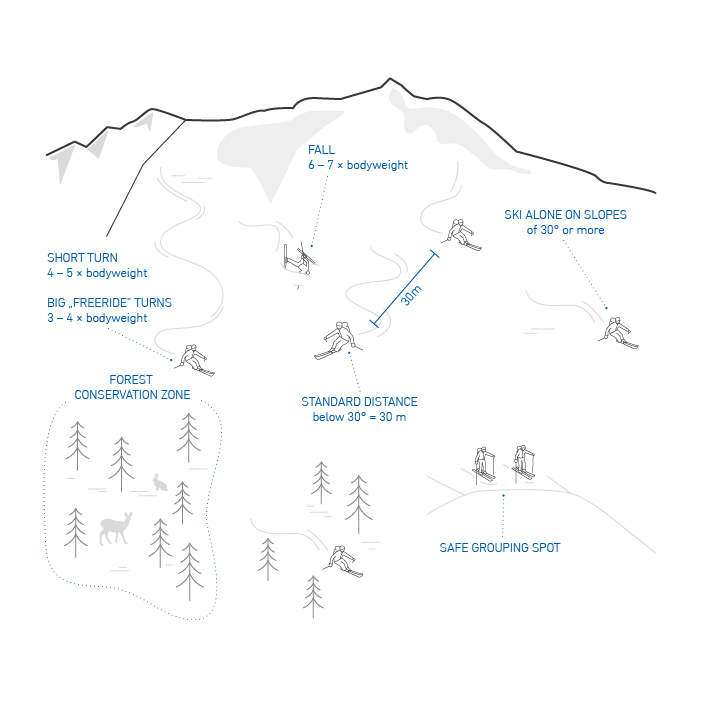

We ask whether there is only one person in the dangerous area because the mortality rate is considerably higher if there are multiple burials. So overall the consequences can be more drastic if there is more than one person in the dangerous area. You could also say: how many rescuers would be available to help how many victims, and how quickly? Because in a rescue, time means a chance of survival. The longer you need to locate and unearth a person, the lower their chances of survival. If only one person is caught in an avalanche, all of the remaining group members can join in the rescue. If several are caught up in it, the search is more time-consuming and there are fewer rescuers available.

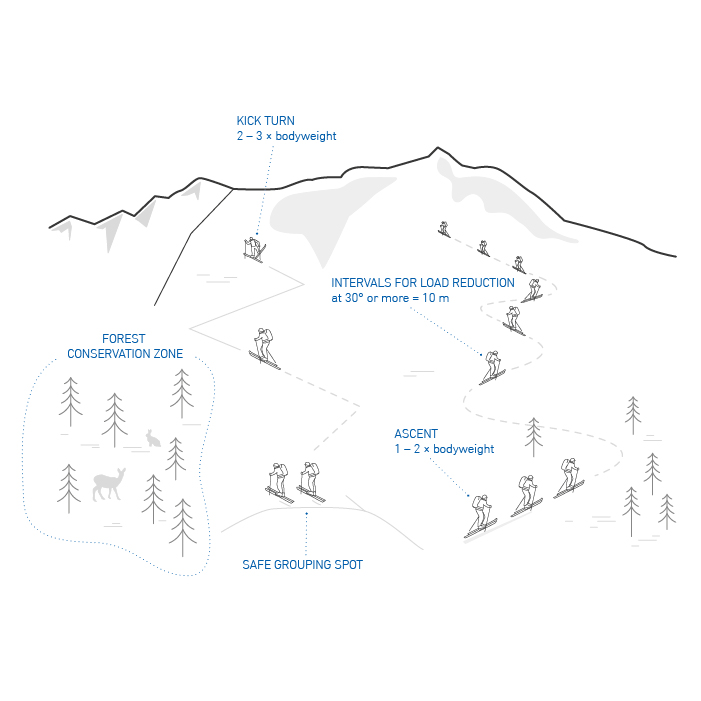

M = Measures

Measures can be used to ease the consequences, e.g. with safety intervals, so that there is only ever one person in the dangerous area. Measures could also decrease the probability of an avalanche, e.g. by introducing safety intervals, making the probability of a slab avalanche less likely.

But measures such as good training, clear communication, a good group structure with considerate, disciplined behavior and observation of group-leading measures (following the same tracks, traveling one at a time, observing limitations, moving cautiously) can also reduce the danger of an avalanche or influence the consequences.

Decisions made as a group, clear communication, a clear group structure, and a harmonious group atmosphere are all points that fall under the “people” factor; they should be included here. And objective factors such as group size, motivation and technical ability.

R = Risk

Risk is the product of the probability of a danger occurring (D = avalanche triggering) and its consequences (C = consequences of an avalanche). Once influenced by measures, the result is “residual risk”. Risk cannot be clearly expressed or quantified with a number. And the “residual risk” accepted by a group can vary considerably (example: “Swedish freerider” compared to “ski touring courses for beginners”).

When evaluating the risk, the picture of two sliders can help: One represents the probability of an avalanche, the other represents the consequences. With the help of this picture, decisions about risk can be visualized and discussed in the group.

If the probability of an avalanche is high, the consequences must be low, and vice versa. In the best case scenario both sliders would be low. If both are mid to high, you should pick an alternative.

Measures during an ascent

The following are recommendations for basic measures during an ascent:

- Actively look out for warning signs

- Use terrain reliefs such as flats and ridges

- Keep away from dangerous slopes and terrain traps

- Keep your distance from each other on steep slopes

- Avoid areas of wind-drifted snow

- Traverse steep slopes as high up as possible

- Constantly assess slope steepness

- Be considerate of other groups and coordinate with them

Measures during a descent

The following are recommendations for basic measures during a descent:

- Ski steep slopes one by one

- Choose safe assembly points

- Agree the order of descent: weaker skiers should be in the middle of the group

- Ski only non-dangerous slopes simultaneously as a group

- In poor visibility and bad snow, ski one after another, following in the same tracks

- Group members should keep an eye on each other

- Observe the buddy principle in a forest: two group members should always watch out for each other

The “people” factor in DCMR

“Problems” or challenges that fall under the “people” factor can also be examined using the DCMR system.

For example, many “objective” aspects of the “people” factor (hard facts) can be directly imbedded into the DCMR method; e.g. the size of the group and ability of the group members play an important role in the probability of an avalanche (D) (initiation) and its consequences (C) (chances of survival).

And even “subjective” factors (soft skills) such as problems with perception, decision traps and group phenomena such as group polarization, in which people in a group are often more willing to take risks, can be assessed using DCMR.

To do this, you ask yourself: How pronounced is it in the current situation (D)?

What are the possible consequences (C)?

What can I do about them (M)?

How high is the risk of an accident or of an accident being likely?

On a ski tour

In order to turn information and knowledge about avalanches into sensible decisions during planning and while in the mountains, we need a decision-making strategy. This will help us come to the most precise possible assessment of our risk. Measures or possible actions people can take to influence the two points – danger and consequences.

Please assign all images to the categories "risk-reducing measures" and "risk-increasing measures".

Matching quiz

Please assign all images to the categories "risk-reducing measures" and "risk-increasing measures".